Seismic methods for medical imaging

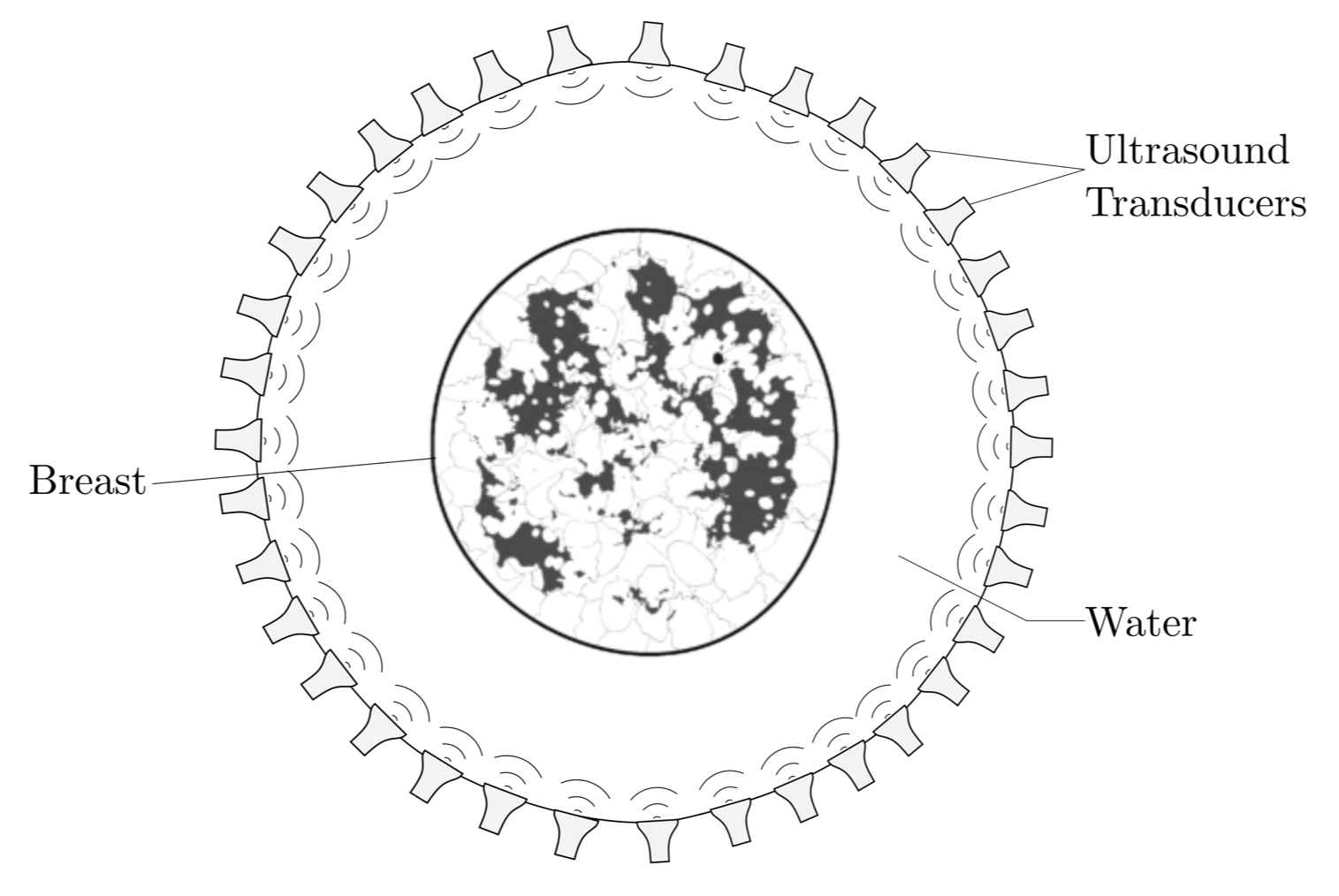

Breast cancer is on of the most common types of cancer in women and it is the leading overall cause of death from cancer [1] . Frequent examination of the breast from a preferably young age is an essential tool to detect and monitor malignant cell regions. As a non-ionizing, low cost method, ultrasound imaging has received increasing attention and imaging platforms that are capable of producing quantitative speed-of-sound images are actively developed [2,3,4]. These imaging devices usually consist of a tank filled with water on which ultrasonic transducers (sources and receivers) are mounted. To acquire data, the breast is emersed into the water bath and ultrasonic pulses are generated by the sources and recorded by the receivers. Generally, these devices employ ring-shaped transducer configurations as seen in Figure 1. that are capable of acquiring reflection and transmission data at the same time with the additional feature to move the array along the vertical axis to acquire several depth slices.

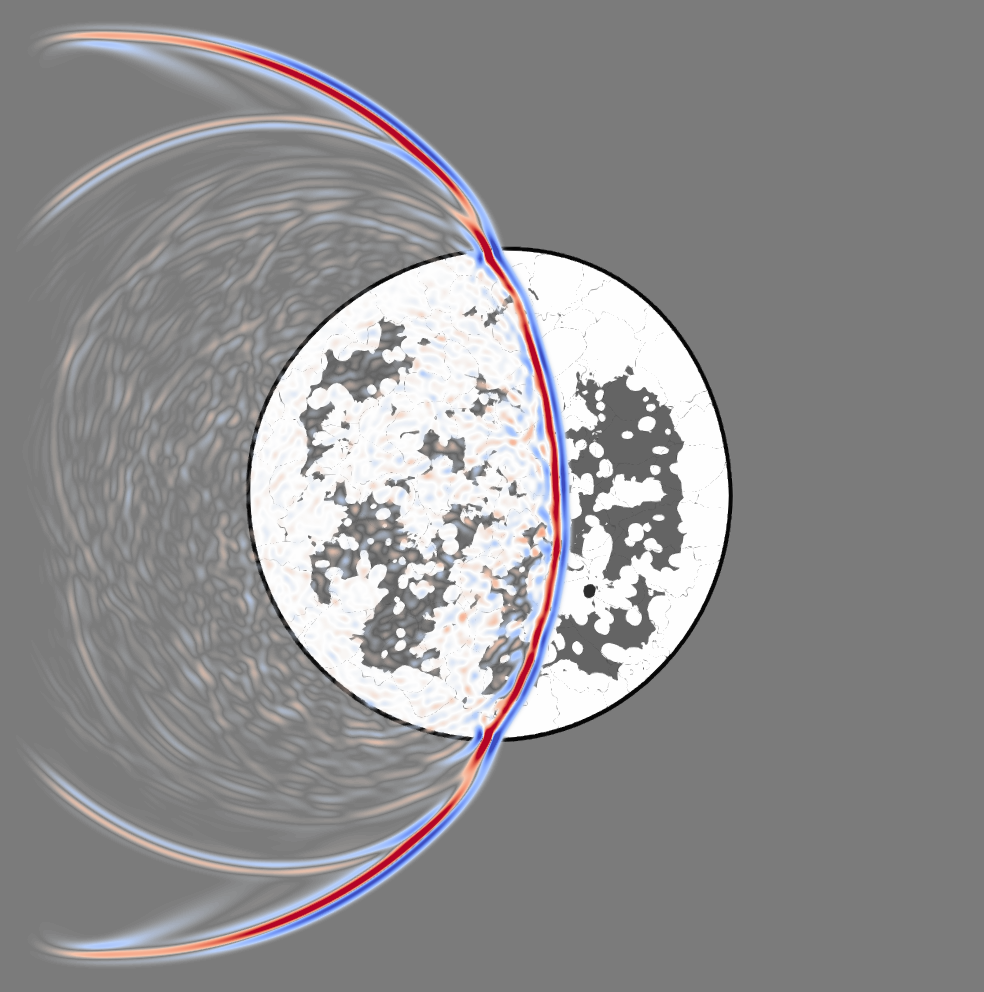

In contrast to mammography where X-rays are used, ultrasonic waves interact heavily with soft human tissue, which can be seen in Figure 2 showing a snapshot of a wavefield propagating through a numerical model of a breast. Therefore, linear approximations so-called ray approximations commonly made for X-ray tomography are inherently incorrect to model the propagation of ultrasonic waves, albeit the approximation can still be justified for smooth media with speed-of-sound deviations less than 5 %. This is the basic assumption taken in conventional ultrasound, which solely uses information contained in the first arriving wave (the prominent blue-red feature) and neglects the scattering information (the lighter features) produced by the interaction of the ultrasonic wave with the tissue structure. In order for ultrasound imaging systems to be competitive with state-of-the-art mammography or MRI imaging technologies, tissue parameters such as the speed of sound or density need to be resolved very accurately. This necessitates the development of more accurate wave propagation models that go beyond conventional ultrasound and use the entire information contained in the waveforms.

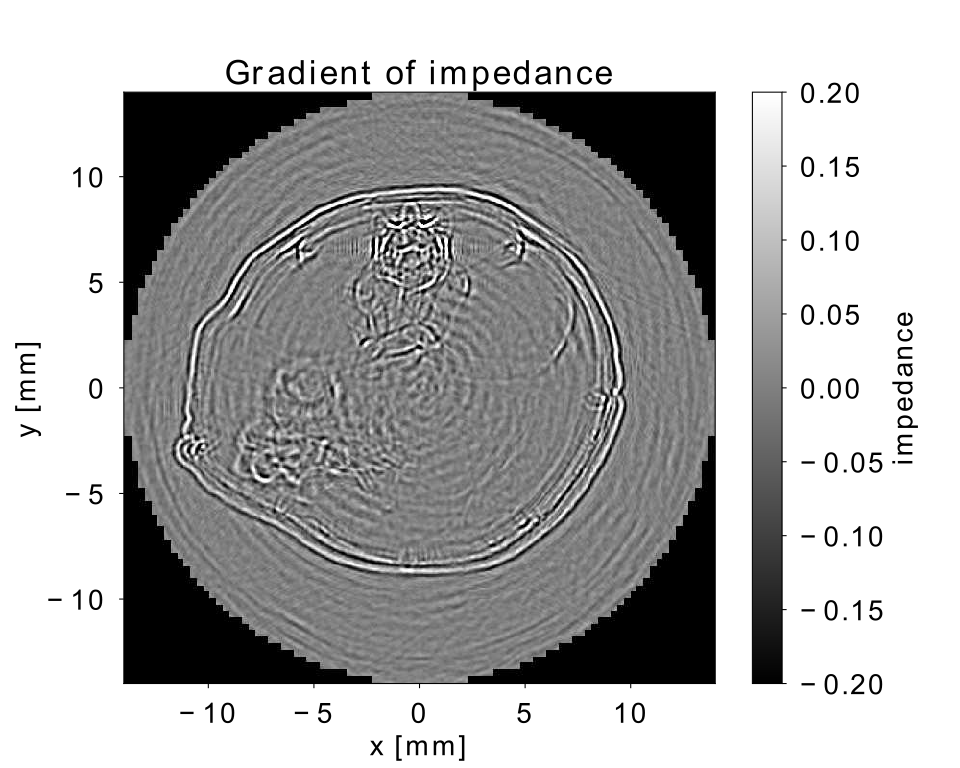

In geophysics, the need for more sophisticated imaging algorithms that “make the most” out of the data acquired in the field has let to the development of wave-based imaging methods that numerically solve the wave equation. From a physical point of view, there exist many similarities between ultrasonic waves that travel though soft human tissue and earthquake waves. Hence the knowledge on how to extract information from a set of wavefield recordings and how to transform this information into images can be transferred from the large scale geophysical application to the small scale medical application. However, the increase in accuracy gained by wave-based imaging methods comes at a price: modelling the entire wavefield is computationally expensive. Our research group uses the the software suite Salvus [5] and the high-performance computer “Piz Daint” at CSCS to simulate the wavepropagation through soft tissue in order to obtain an image of the tissue structure. Currently, we are seeking to apply our methods to real life data sets with a first attempt to reconstruct an image of a cross-sectional slice through a mouse acquired in-vivo with a transmission-reflection optoacoustic ultrasound device [6] targeted to characterize tumors in mice. With our imaging procedure, we aim to resolve the different structures including the vertebrae and the soft abdominal tissue in order to differentiate cell regions. With this, tumors can be detected and classified as malignant or benign based on the reconstructed speed-of-sound values. Figure 3 shows a qualitative image of the impedance contrast thus displaying the location of interfaces between different materials such as bone and tissue or skin and water. Taking this image as a starting point, the aim is to generate a quantitative image displaying the speed-of-sound structure at a comparable resolution.

[1] Siegel, R.L., Miller, K.D., and Jemal, A. (2019). “Cancer statistics”, CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:7–34.

[2] Duric, N., Littrup, P., Schmidt, S., Li, C., Roy, O., Bey-Knight, L., Janer, R., Kunz, D., Chen, X., Goll, J., Wallen, A., Zafar, F., Allada, V., West, E., Jovanovic, I., Li, K., and Greenway, W. (2013). “Breast imaging with the Softvue imaging system: First results,” in Medical Imaging 2013; Ultrasonic Imaging, Tomography, and Therapy.

[3] Gemmeke, H., Hopp, T., Zapf, M., Kaiser, C., and Ruiter, N. V. (2017). “3D ultrasound computer tomography: Hardware setup, reconstruction methods and first clinical results,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 873, 59–65.

[4] Malik, B., Terry, R., Wiskin, J., and Lenox, M. (2018). “Quantitative transmission ultrasound tomography: Imaging and performance characteristics,” Med. Phys. 45, 3063–3075.

[5]Afanasiev, M., Boehm, C., van Driel, M., Krischer, L., Rietmann, M., May, D. A., Knepley, M. G., and Fichtner, A. (2019). “Modular and flexible spectral-element waveform modelling in two and three dimensions,” Geophysical J. Int. 216(3), 1675–1692.

[6] Mercep E., Herraiz J.L., Dean-Ben X.L., Razansky D., Transmission–reflection optoacoustic ultrasound (TROPUS) computed tomography of small animals. Light: Sci Appl, 2019.